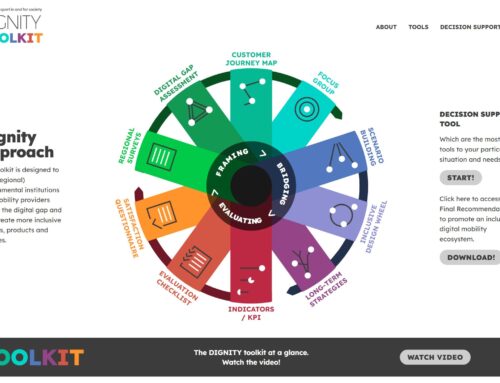

The first phase of the DIGNITY project is “framing the digital mobility gap”. What is the aim? To identify what is missing in digital mobility and provide the necessary information to help develop services that meet the real needs of potential end users. To get a complete picture, DIGNITY looks at the mobility gap from three different, but interconnected, perspectives:

- Micro level: focusing on citizens and their needs

- Meso level: looking at technology and market offers

- Macro level: including the viewpoint of public authorities

One of the tools DIGNITY utilises is its self-assessment framework. This set of guidelines and forms can be autonomously used by organisations to conduct their own systematic assessments.

What happened when the self-assessment was conducted in Barcelona?

MICRO Results show that 94% of Barcelona’s population has access to the Internet, and 98% have a smartphone. These are sizeable numbers, but on the flip side, 27% of respondents say they have little or no confidence in actually using the internet. So citizen technology skills still need improvement, and solutions should also be adapted to more closely fit their requirements and abilities. Additionally, enhanced offline alternatives and low-tech tools should be made available.

MESO Barcelona has a number of digital mobility products and services. The city is becoming increasingly digitalised, and as a consequence, new market players are emerging to offer relevant solutions. One example is the Smou app, which provides mobility information and services – such as renting bicycles, paying for parking and recharging electric vehicles.

Great news, but the majority of Barcelona’s numerous mobility services are destined for the general public, and services specifically designed for vulnerable-to-exclusion groups are still lacking.

MACRO The DIGNITY self-assessment framework sets out three dimensions to help understand policies related to the digital gap:

- Governance structure

- Regulatory framework

- Budget and outreach programmes

Barcelona has policies and regulations that make reference to digital mobility products and services that factor accessibility, equity, and citizen involvement into their decisions processes.

However, a regulatory framework that addresses the connection between digitalisation in transport and social inclusion is still missing. The planned policies and documents do not address groups such as migrants or people with low levels of education. The same is seen in budget and outreach programmes, which mostly target older groups with low incomes, but make lesser reference to other vulnerable collectives.

Overall, it emerges that there is a room for improvement with regards to the governance and regulatory framework in Barcelona. There is need for leadership and departments that focus on topics related to transport, digitalisation and social inclusion, and policies, budgets and programmes should take all vulnerable-to-exclusion groups and their needs into consideration.